Few places on earth have the same sense of adventure and discovery as the Rocky Mountains. With the exception of the Alps, Andes, Himalayas, and of course Antarctica. In this article, I would like to momentarily divert my attention from the Rocky Mountains to the vast frozen continent of Antarctica.

People have been desperate to understand and explore Antarctica since its tentative discovery by Captain Cook in the 1770s. Eventually, his sighting was confirmed by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen in January of 1820, when he saw the Antarctic ice shelf. By 1840 the Wilks expedition established that Antarctica was indeed a continent. Nations fell upon themselves to begin to understand, explore, and lay claim to this harsh and frozen wasteland.

Early explorers used the methods of Native Americans to explore the Antarctic Ice shelf. Specifically, they borrow techniques from the Inuit People of Alaska; such as sled dogs and thermal-insulated clothing. However, food was scarce and these methods would not sustain the explorers very long. In order to explore deep into Antarctica innovation and invention were required.

Each successive expedition and encampment brought with them experimental equipment and techniques. All designed to better explore and conquer the unforgiving and otherworldly environment of Antarctica. Innovation would not prove easy; specifically, early vehicles and motorized equipment had a very hard time in these conditions.

Automobiles were still in their infancy during early explorations and to this day equipment must be specially designed to withstand and operate in constant sub-zero temperatures. Each attempt to introduce vehicles to the difficult landscape and temperatures suffered faults, fails, and numerous setbacks.

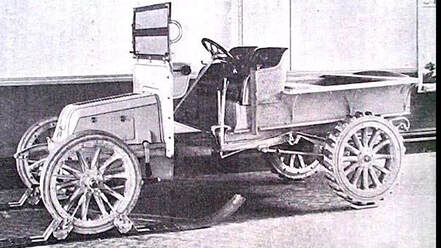

British explorer Ernest Shackleton in the Nimrod expedition managed to bring the first automobile to the continent in 1909. The expedition boasted a specially designed vehicle that was donated by the defunct British automaker, William Beardmore and Company. The vehicle replaced the front tires with skis and the rear tires with large cogs. It was ultimately unsuccessful in navigating the deep snow and ice. For that matter, it could not be started at sub-zero temperatures or run for an extended period of time in the cold. Like most things in Antarctica it was repurposed and was reused as a wagon. For the remainder of this expedition, they relied on traditional sleds.

One year later; in 1910, a British Naval officer named Robert Falcon Scott saw potential in Ernest Shackleton’s idea and further innovated upon this concept during the ill-fated Terra Nova expedition. He and his engineer Reginald Skelton pioneered and advanced the concept of motor-driven sleds during their race to the south pole. But they later abandoned the idea for a caterpillar track to make it across snowy surfaces. This innovation edged us closer to something resembling the workings of a modern snowmobile.

By 1911 Australian explorer Douglas Mawson set his sights on Antarctica. During his visit to the continent, he intended to bring the first airplane. Unfortunately, the plane crashed during an airshow demonstration before Mawson ever left for the expedition. Making the best of a bad situation and ever-the-showman, Mawson had the plane hastily reconstructed into what he called an experimental “air-tractor”. This was basically a tractor on skis, made out of the old Vickers airplane. This was also unsuccessful. The engine was removed and sent back to Vickers, in England. The rest of the plane was abandoned and claimed by the arctic snowdrifts. Similar to the motorcars, sleds, and vehicles that came before it. But these failures are not uncommon and it is only through failure that science can learn what does or does not work. As they say, “the road to success is paved in failure.” or “Fail fast and learn slowly.”

Flash forward 20-years to the 1930s Antarctica was to be home to one of the most incredible and ambitious vehicles ever built. The Arctic Snow Cruiser was impressive not just in its incredible size and innovative features but was also notable as an automotive masterpiece.

But before the Arctic Snow Cruiser could make its way to Antarctica the groundwork was laid by Rear Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. from the United States Navy. Byrd is most well known for his successful flights over both the North and South Poles. Although his claim to the North Pole flight was later disputed by the Smithsonian Institute. None-the-less he was an accomplished arctic explorer who was a part of the crew who completed the first transatlantic flight in 1919. Eventually, Richard Byrd was the recipient of the Medal of Honor, which is the highest honor of valor given by the United States.

Through the 1920s Byrd had been organizing American expeditions into Antarctica. He had established two bases on the continent; “Little America” (in 1929) and “Little America II” (in 1934).

By the end of the 1930s war was threatening to engulf the world as World War II was ramping up. Germany as well as the Japanese empire were increasing their activities and territorial ambitions around the continent of Antarctica. Because of this president, Roosevelt sought to make the US presence in Antarctica permanently established.

Roosevelt’s increased interest in the continent drastically improved Richard Byrd's third expedition to the antarctic. It grew out of it’s small and privately funded roots into a well-funded mission. One that looked to maintain United States bases on both sides of Antarctica. It was organized jointly by the US Department of State, The US Navy, The Department of the Interior, And the US Department of War. The base was named “Little America III” and demonstrated the United State’s interest and dedication to the arctic. A spirit that continues to this day.

This was the largest expedition the world had seen so far and nations waited with anticipation to discover the final scale of this grand expedition. However, few could guess what innovation was about to roll onto the stage. This is because Byrd and his team drew from the past experiences and failures of the equipment used and sought to design a vehicle that could incorporate the best elements of its predecessors. He had considerable success with caterpillar tracked vehicles in his previous expeditions. In fact, he credited their use directly for saving his life when he had been stranded alone in a remote outpost, during his second expedition.

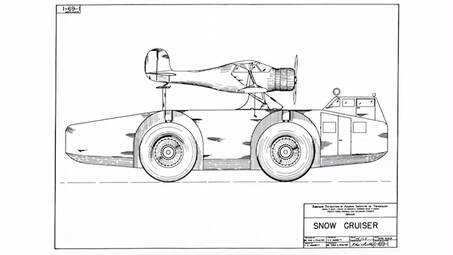

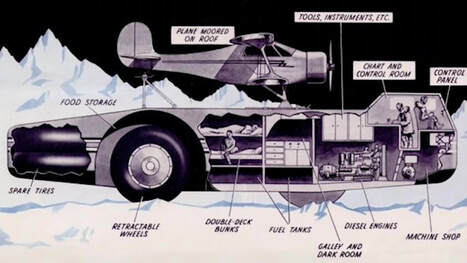

Byrds deputy, Dr. Thomas Poulter has spent the years since researching ways to adapt the motorized tractors they used to be better suited for sustained use at sub-zero temperatures. Working with the Armor Institute of Technology; in Chicago, now the Illinois Institute of Technology, Poulter designed what he called “The Snow Cruiser”. His design was a 55 feet (16.7 m) long, 25 feet (7.6 m) wide, 37-ton giant. It was designed to have a range of over 8,000 miles (12,874 km) and could sustain a crew for up to a year on the ice without resupplying. The monstrous machine was powered by two specially designed diesel-electric engines and was designed for a maximum speed of 55 miles per hour.

The Snow Cruiser was crammed with clever innovations; such as its four 10-foot tall balloon-like Goodyear tires. The tires and wheel assembly could be moved individually and lifted clear of crevices and other obstructions. Additionally, they could completely retract them into the chassis of the cruiser. Add to that, the tires had an innovative system that was designed to keep the rubber of the tires warm, by reusing the heat and exhaust from the engine bay.

Inside the Snow Cruiser featured all of the facilities a crew of four could need for exploring and living in the Antarctic landscape. It was complete with a control room, a machine shop, a galley, a dark room, extra tanks for fuel, food storage, crew quarters, and it even had space for two gigantic spare tires. The range of gadgets and capability were nearly endless.

The top of the Snow Cruiser sported a cradle for an aircraft. The plane boasted a range of about 300 miles (482 km) and acted as a scout for the cruiser. The aircraft could be loaded and unloaded through the sloped back of the cruiser.

This was without a doubt the most ambitious vehicle of its time. But before it could be built it was up to Thomas Poulter to justify how this vehicle would revolutionize arctic exploration. Eventually, the US gave the Snow Cruiser project the green light and handed over $150,000 a value of $2.3-Million at that time.

The Snow Cruiser was seen by the US congress as the crown jewel of an arsenal of new tools they looked to deploy in what was now the United States' fourth expedition to Antarctica. Especially because other countries' interests and competing claims to the region began to pick-up. While the cruiser was being built Germany had deployed a large catapult ship to the region and begun to operate survey planes around Antarctica. “Claiming” large tracks of land in the name of Nazi-Germany.

In an effort to further impress upon Congress and justify the large expedition budget Poulter began to boast about how the craft was designed to cover 500,000 square miles during an Antarctic summer. A claim that was a bit sketchy, but plausible nonetheless. With the international competition now worrying lawmakers, the Antarctic Snow Cruisers construction was expedited.

It created a national sensation as it raced off the factory-floor and across 1,000s of miles or roadways. Making its way from Chicago Illinois to Boston Massachusetts. At the time the Cruiser was wider than most of the nation's roads. To navigate around this, they executed a carefully orchestrated plan which involved closing highways and clearing traffic from the roadways ahead of the Snow Cruiser. It was a parade-like atmosphere, a sensation that was driven home by the motorcade of police that both preceded and followed the massive automobile. At one point the cruiser attempted to navigate over a creek and did get stuck for a time. While this was not a very encouraging moment, the engineers used this as an opportunity to test the independent suspension in a warmer climate.

None-the-less it made it back onto the roadway and to the Boston docks on time, where it was loaded onto the supply ship, “The North Star”. Along with Food, spare tires, several tanks, prefabricated huts, and everything they would need to live for over a year in Antarctica. In order to fit the vehicle, the entire rear-wheel section was removed and stored elsewhere. Once this was completed it was secured to the deck of the North Star. The captain had concerns about the weight being distributed properly, but after Byrd's insistence, they permitted the cargo aboard. With much fanfare the North Star and Arctic Snow Cruiser inches into the Pacific Ocean. After a few nervous moments, the captain gave his approval and set sail in November of 1939.

As it made its way, the New York Times surmised that: “The Snow Cruiser has connected West Base with East Base; or has rolled along that coast which no man has surely seen… or, perhaps, made itself a laboratory-based, for a period of months, at the Pole itself”. Only a few of their hopeful claims would come to pass. While it may have been a bit presumptuous of the New York Times, it goes to show just how enthusiastic Americans were about the Snow Cruiser.

The expedition reached the site of little America III in January of 1940. As the Arctic Snow Cruiser made its way off the North Star and on to a simple wooden ramp. The ramp began to give away. Leading to a tense moment when Byrd was nearly thrown from the roof of the cruiser. Fortunately, Byrd was able to run to a handhold and secure himself. Meanwhile, Poulter, who was at the wheel hit the accelerator, leaping the cruiser forward and on to the relative safety of the ice.

Once on the ice, they found that the vehicle was much slower than anticipated. To correct this issue, they outfitted the Snow cruiser with two spare tires for additional traction. But this design change gave way to a new problem, it was now very bouncy. In fact, it earned itself the nickname, “bouncing Betty “. Additionally, the vehicle was already at its maximum design weight. With the added weight the innovative diesel-electric drivetrain was now underpowered. Interestingly, they found that in this configuration the cruiser was fastest in reverse. So, they simply started driving it backward. However, the prospects for long-range travel didn't look good and the crew was forced to abandon these efforts.

Making the best out of the situation, they used the airplane to survey large sections of the ice shelf that Little America III rested on and was able to scout into the continent.

While it’s primary purpose was not successful, it did find success as a stationary laboratory and served as the most luxurious and modern crew quarters on the continent. The innovative heating system and insulation material proved to be very effective and was integrated into future projects. However; the great Arctic Snow Cruiser was forever assigned as a stationary part of Little America III. This is how it remained until the western base was decommissioned in 1941. The entire base was evacuated later that year as the concentration of troops and funding moved to defend the world from the increasing German, Japanese, and Italian aggression. At that time the Arctic Snow Cruiser was buried with snow and abandoned.

After World War II, In 1946, during an American expedition called “operation high-jump,” the team located the abandoned base and the giant snow cruiser sitting exactly as it had been left. The team of explorers said the vehicle was in remarkably good condition. Saying “only air in the tires and a basic servicing would have had it up and running again”. However; nothing further was done and the Arctic Snow Cruiser was once again closed up and left to the elements.

In 1958 the cruiser made its final appearance on the world stage. This time it was an international expedition that completely uncovered the snow cruiser from its tomb of ice using a bulldozer. It was hidden under several feet of snow, but a long bamboo pole left by the previous expedition still marked the location of the Snow Cruiser. Inside the cruiser was again reported to be exactly how it was leftover two decades ago. Complete with newspapers, magazines, and cigarettes still placed as if waiting to be picked back up. This group of explorers was likely unaware at the time, but they were the last people to see the incredible Arctic Snow Cruiser.

Or were they? Could it be possible that the snow cruiser is still sitting under the snow and ice of Antarctica? Somewhat recently a team located pieces of Douglas Mawson’s “air-tractor”. They were discovered under 9 feet of ice (3 m). Relics from old expeditions are found regularly to this day. Many of these items are preserved by the sub-zero temperatures and ice encasement. Some feel that the Soviets may have recovered the Snow Cruiser after it was unearthed in 1958. While this is very plausible, it is unverifiable and remains just a theory. So to answer my question, “Could it be possible that the snow cruiser is still sitting under the snow”? This is likely not the case.

This is because in February of 1963 a US Navy icebreaker ship spotted an unusual streak of brown amongst the blues and whites of passing icebergs. As they edged closer they were amazed to find what appeared to be the remains of Little America III protruding from the iceberg. The ship launched its helicopter to take aerial photos. It even landed on the iceberg in an attempt to access the base. Ultimately they were unable to find a way in, however; they could clearly make out the remains of tents, fabric, and prefabricated huts. Huts that were strikingly similar to huts that Byrd used during his expeditions. The icebreaker was able to verify that cans of food and equipment were still neatly packed on the shelves; much like the team who visited Little America III in 1958 described. Five telephone poles and antenna fitting still stood above the snow. Notably, two bamboo marker poles were still in place on the surface.

It is a safe assumption that the ruins found by the Navy were that of Little America III. With that assumption taken into account, it means that the majority, if not all of the base has broken off the Antarctic ice shelf and has drifted away into the ocean. We do not know what part of the base that iceberg held, but it is entirely possible that one of those bamboo markers stood over the buried Arctic Snow Cruiser. It has likely drifted out to sea and eventually sunk to the sea bed. Though, a part of me doesn’t accept that this was its fate. I still hold hope that one day she will emerge jutting out of an old iceberg or maybe parched on the side of the Ross ice shelf. Perhaps it will be dredged up from the seabed by a commercial fishing operation. One thing is certain though, despite its failure to connect the East and West bases it succeeded at igniting the American spirit, imagination, and most of all innovation.

0 Comments

|

AuthorThank you for visiting! This is a collection of media from the lost and abandoned corners of the world. Please have a look around, I hope you enjoy. Archives

April 2022

Categories

All

|

Libraries |

Support |

|